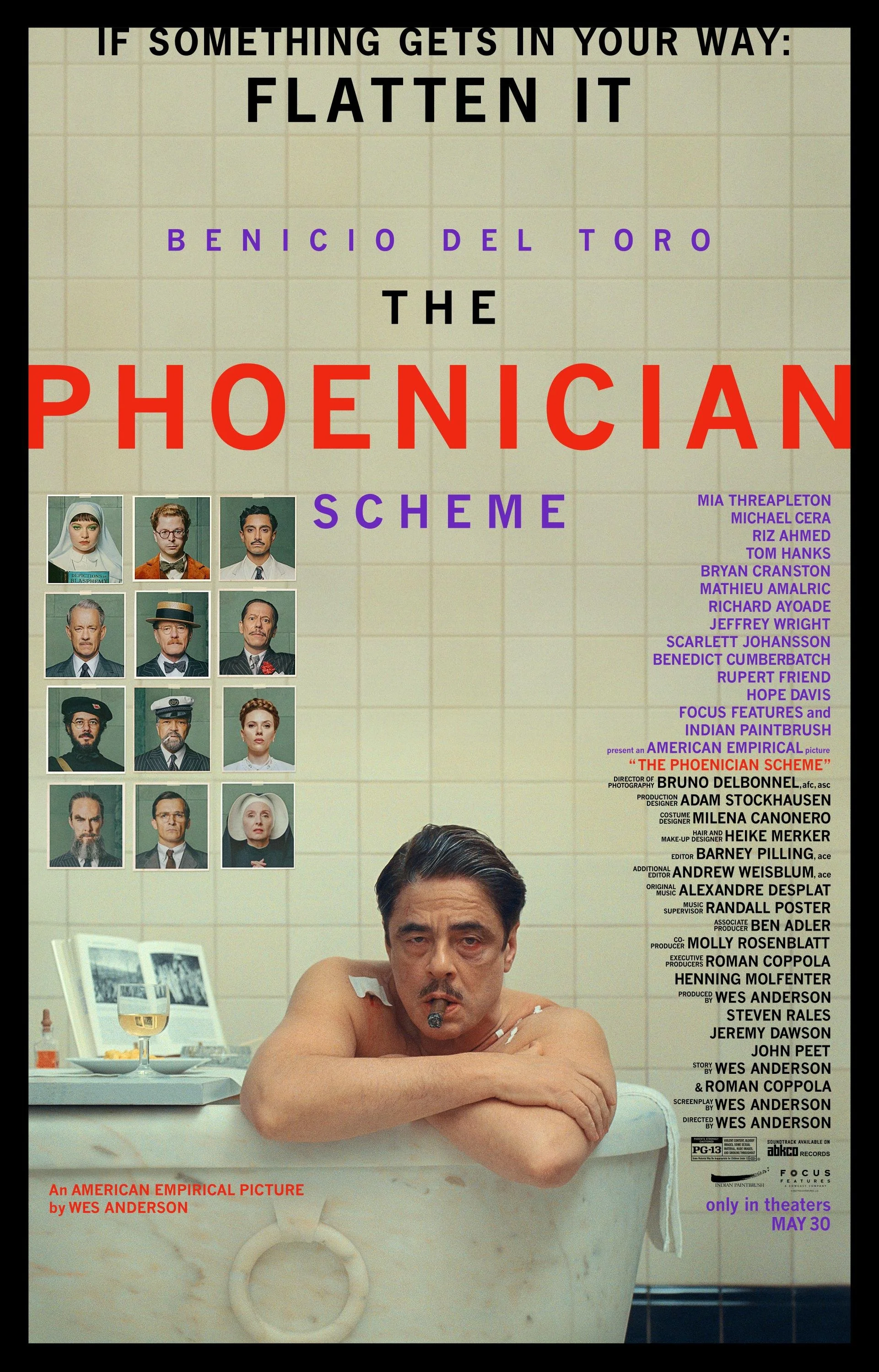

The Phoenician Scheme (2025)

dir. Wes Anderson

Rated PG-13

image: ©2025 Focus Features

Legendary film critic Pauline Kael famously never saw the same movie twice. It was part of her ethos as a critic. She believed that one’s initial reaction to a movie was the purest one, and that seeing a movie more than once would dilute the spontaneous emotional response of the viewer. Surprising absolutely no one, I find this idea utterly baffling. It is certainly the philosophy of someone who lived the majority of her life at a time when seeing a movie after its initial theatrical exhibition was close to impossible.

I bring up Kael’s eccentric take on examining art – could you imagine the same standard being applied to great paintings or musical compositions? – because I’ve discovered that the films of Wes Anderson tend to blossom more fully for me on a second viewing. For Anderson’s masterpiece The Grand Budapest Hotel, it took me actually sitting down and reading the screenplay for the full force of Anderson and Hugo Guinness’s tale of nostalgic yearning to hit me. I felt adrift and disconnected from Anderson’s delightful Asteroid City until a second viewing helped me unlock its considerable charms.

The extensive throat-clearing I’ve engaged in above is a way to communicate that I’ve only had a chance to see Anderson’s latest, The Phoenician Scheme, once before crafting this review. I should have known better and set aside time to screen it twice before dueling with the blank page. But life, the day job, and acute depression brought on by the current state of the world conspired against me.

A single viewing of The Phoenician Scheme left me cold and feeling distanced from what Anderson is doing this time around. Rest assured, though, that every sentence I write comes with an implied asterisk that represents my curiosity of how a second screening might change my opinion.

Like some of Anderson’s other troubled protagonists – Royal Tenenbaum and Monsieur Gustave H. come immediately to mind – the reluctant patriarch at the center of The Phoenician Scheme, Anatole "Zsa-Zsa" Korda, is a bit of a son-of-a-bitch. A ruthless arms dealer and industrialist who has survived countless assassination attempts at the hands of both governments and business rivals, Korda knows no bounds when it comes to enriching himself, often at the expense of others.

In what feels like a nod to someone like the odious Elon Musk, Korda has also secured the next generation of his empire by siring ten children, nine boys and one girl. He has steadfastly ignored his children in pursuit of his business ambitions; the boys all share a dormitory across the street from Korda’s home. He gave up his only daughter, Liesl, for adoption, and her adoptive parents promptly turned their new family member over to a convent to be raised as a novitiate nun. Now a young woman in her early twenties in the year 1950, Liesl harbors nothing but distain for her estranged father.

Korda is determined to win over Liesl by making her his sole heir when the latest failed assassination attempt against him causes him to reëvaluate his life. During the near-death experience of falling to the ground after a saboteur plants a bomb on his plane, Korda visits the afterlife – the first of several haunting black-and-white heaven sequences reminiscent of British filmmakers Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's 1946 film A Matter of Life and Death – and is judged on his worthiness to enter heaven.

(Upon this first afterlife sequence, I was immediately reminded of 79-year-old Donald Trump’s recent public ruminations on the unlikelihood of his being allowed into heaven once he checks out of Hotel Planet Earth.)

I realize that I’m reading my own obsessive preoccupations into Anderson’s picture by likening Korda to Musk and Trump, but it’s not wholly without merit. Anderson, with the help of frequent collaborator Roman Coppola on the story, loosely based Zsa-Zsa Korda on early-20th century Armenian oil magnate Calouste Gulbenkian, as well as other powerful industrialists of the era. There is a corollary between rich and powerful men of that bygone era and our current one.

And that might be what’s holding me back from fully embracing The Phoenician Scheme. The most successful of Anderson’s flawed heroes are the ones who are erudite, sophisticated, and urbane, but who are also fuck-ups in one way or another. Royal Tenenbaum, for instance, could be uncharitably described as a grifter. His late-in-life attempt to mend fences with his estranged family comes after years of not very successfully flim-flamming his way through life.

By contrast, Zsa-Zsa Korda is an amoral titan of industry – and one of those industries is selling death and destruction via weapons of war – who has achieved every goal to which he’s set his mind. At the heart of The Phoenician Scheme, much like with Rushmore, The Royal Tenenbaums, and The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, Anderson’s protagonists realize that all of their scheming for wealth and reputation has blinded them to what really matters in life, the love and affection of those closest (if only in terms of blood relations) to them. They then set about correcting the oversight and making amends with those who they’ve treated shabbily.

That’s a long-winded way of expressing that The Phoenician Scheme feels, more than any of Anderson’s previous efforts, like well-worn territory for the director. He’s repeating himself here in a way that doesn’t offer any new insights into his philosophy on life or familial relationships. Despite its eccentricities, rigorous formalistic technique, and droll humor, I was ultimately bored by The Phoenician Scheme. Regardless of how many times I’ve seen his previous works, this was a new sensation for me upon viewing a Wes Anderson movie.

Like other of Anderson’s films, The Phoenician Scheme is, at heart, a road movie. Our flawed protagonist embarks on a quest to right his past wrongs, and learns valuable life lessons along the way, making him a better person. I felt the formula this time, and each stop along the route felt more like an excuse to introduce ever increasingly eccentric characters than it was about Zsa-Zsa’s ethical and emotional arc.

That doesn’t mean that encountering those increasingly eccentric characters isn’t an absolute hoot. After he convinces Liesl to team up with him – which has more to do with her desire to learn who exactly murdered her birth-mother than any attachment she has to her father – Zsa-Zsa and his daughter seek to secure funding for the former’s greatest business endeavor when his enemies enact a plan to financially ruin him.

His Phoenician scheme involves modernizing and revolutionizing, for his own profit, the infrastructure of Phoenicia using slave labor. When his political and business foes cause a sharp spike in the building materials Zsa-Zsa will need to pull off his scheme – a delightful Andersonian touch involves a crash course for the audience in the virtues of “bashable rivets” – the tycoon must convince each of his investors to up their stake in order to offset the now-increased costs.

Anderson’s usual repertory company, with some notable new faces, fill out his cast of oddballs and eccentrics to delightful effect. Bryan Cranston and Tom Hanks, relative newcomers to the Anderson fold, are pitch-perfect as basketball-obsessed Californian brothers who condition their increased investment on the outcome of a game of H-O-R-S-E. (Seeing the two near-septuagenarians Cranston and Hanks earnestly wearing Stanford and Pepperdine (respectively) athletics gear is amusing.)

Tom Hanks (left) and Bryan Cranston (right) in a still from The Phoenician Scheme.

Riz Ahmed takes his first swim through Anderson’s filmography in a brief scene as Prince Farouk, the crown prince of Phoenicia. Mathieu Amalric, as gangster Marseille Bob, got hearty laughs out of me when his character becomes indignant at a group of guerilla fighters who destroy the beautiful chandelier in his nightclub during a robbery.

Anderson telegraphs his adoration for Bill Murray, perhaps his longest-sustained creative partner, by casting him as God in the film’s heavenly sequences. The inimitable Jeffrey Wright brought a smile to my face each time he injected “man” into his dialog as Marty, another of Zsa-Zsa’s investors we meet along the way.

With The Phoenician Scheme, Anderson teams up with Michael Cera for the first time, and the result is a twee match made in heaven. Cera plays Bjørn, an entomologist whom Zsa-Zsa hires as a tutor for his children, and who later becomes the patriarch’s administrative assistant. Bjørn holds some secrets of his own, and Cera’s transformation when the character’s true motives are revealed is comic brilliance.

Benicio del Toro and Mia Threapleton, as Zsa-Zsa and Liesl, could almost be thought of as delivering a joint performance, their characters and arcs are so closely entwined. Del Toro is gruff, almost impenetrable, as Zsa-Zsa. The character repeatedly invokes the phrase, “Myself, I feel very safe,” almost as an incantation against misfortune. Threapleton holds her own in each of her scenes with del Toro. Liesl’s cold and righteous indignation becomes the real obstacle that Zsa-Zsa must overcome to truly find the inner peace he seeks.

That last observation, and how it leads to and shapes The Phoenician Scheme’s final minutes, is emotionally earned by what’s come before it. But, as I mentioned at the top of the review, I felt the formula here more than I have with any previous Wes Anderson movie.

But who knows how a second helping of The Phoenician Scheme might change my perspective.

Why it got 3.5 stars:

- It’s got everything I love about a Wes Anderson project, but The Phoenician Scheme was his first that I felt slightly bored by. I felt like I knew exactly the route we would take and exactly where we would end up within the first twenty minutes of the movie.

Things I forgot to mention in my review, because, well, I'm the Forgetful Film Critic:

- This is certainly the most violent movie Wes Anderson has ever made. The opening plane crash features a bonkers bit of horror that David Cronenberg would appreciate.

- There’s a very odd bit during the heaven sequences in which God (played by Bill Murray) pronounces that slavery is “damnable to hell.” God should really check his own book. He’s super into slavery in the Bible.

- Despite my less-than-enthusiastic take on The Phoenician Scheme, something as simple as Anderson’s beautiful rendering of a necklace — with the help of Bruno Delbonnel’s gorgeous cinematography — in a spotlight utterly beguiled me.

Close encounters with people in movie theaters:

- I missed the initial theatrical release of The Phoenician Scheme and caught up with it on Peacock+. It’s no longer available on that service (despite only being parked there for a few months). You can currently find Anderson’s latest for free with an Amazon Prime subscription, or for rent and sale on most VOD platforms.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

The FFC’s political soapbox

What’s the over/under on how many weeks until we actually invade Venezuela to steal their oil? As of this writing, the United States government has destroyed 27 boats, killing 99 people, while providing zero evidence of wrongdoing. This isn’t even a war crime; it’s plain, flat-out murder. This is not normal. None of this is normal.