Sitting in the Plaza Theater, awaiting the start of the third annual It Came from Texas film festival, I heard The Laugh. Festival Director Kelly Kitchens was in the house; her unmistakable and infectious giggle echoed around the room. (As someone who has at times been identified solely by my laugh, I appreciate the exuberance of a good guffaw.) I had already spied ICFTX’s resident film historian, Gordon K. Smith, donning a period-appropriate 1930s-era fedora in anticipation of the fest’s opening screening, 1967’s Bonnie and Clyde.

The theme of this year’s fest, True Texas Tales, delivered to the audience, among other things, Depression-era bank robbers, an East Texas murder scandal, an inspiring account of Black excellence in the Jim Crow South, and a (highly whitewashed) look at the state’s most iconic location and historical event.

It had been almost a decade since I’d screened Bonnie and Clyde. The film was part of a 50th anniversary series focusing on the movies of 1967 that was offered for free and to the public in 2017 from Southern Methodist University’s film studies department. I’ve now seen a handful of times the movie that cemented Warren Beatty, Faye Dunaway, and Arthur Penn’s legacy of helping to spark the New Hollywood movement of the 1970s. So far, Bonnie and Clyde has lost none of its immediacy or ability to fascinate.

The opening minutes of Bonnie and Clyde feel straight out of the French New Wave. The movie’s final sequence, dramatizing the bloody end of the real-life bank robbers, was shockingly violent for 1967. The breathtaking editing in that sequence is on par with the famous 52 cuts that make up the shower scene in Hitchcock’s Psycho.

Although the end of the Hollywood Production Code was already in sight by the time of Bonnie and Clyde’s release – the Motion Picture Association of America (or MPAA)’s new content ratings system, still in use today, would be implemented in 1968 – but it’s impossible to overstate how completely Bonnie and Clyde’s graphic violence and overall sensibility altered the filmmaking landscape.

Bosley Crowther, who served as the film critic at The New York Times for 27 years, hated Bonnie and Clyde so much that he ended up writing not one, not two, but three separate negative reviews for the film. He was pushed out as the Times critic in 1968, with speculation swirling that it was because the culture had left him behind when positive reviews for Bonnie and Clyde appeared in Time and Newsweek.

The second half of Friday’s double bill was another version of the infamous star-crossed lovers’ story. A much, much worse version. The Other Side of Bonnie and Clyde is a kinda/sorta documentary narrated by Burl Ives(!) and from the mind of Texas-based schlockmeister Larry Buchanan. Released in 1968, it’s a cheaply made attempt by Buchanan to make a quick buck off of the phenomenon of its predecessor.

Luckily, we had local MST3K-style comedy troupe Mocky Horror Picture Show in attendance to deploy strategically timed jokes over the lackluster action on the screen. To be totally honest, The Other Side of Bonnie and Clyde was so tragically unengaging that I barely remember anything about it. That’s not the case with the MHPS show. I got a Pete-Hegseth-is-a-dangerous-drunk joke, which I enjoyed, and an expertly timed Rudolf the Red-Nosed Reindeer riff in honor of Ives’s most iconic performance as a kindly snowman.

**********

Saturday morning got off to a lighthearted start with Bernie, director Richard Linklater’s true-crime tale told via an intoxicating mix of documentary and conventional narrative storytelling. Before the screening, Skip Hollandsworth, who wrote the original Texas Monthly article that the movie was based upon – as well as contributing to the screenplay alongside Linklater – played up his dogged reporter sensibility to regale us with anecdotes about gathering information for the story, as well as his experiences writing the screenplay with Linklater.

Journalist Skip Hollandsworth (left) and ICFTX Festival Director Kelly Kitchens (right) (photo by the author)

The small East Texas town of Carthage is scandalized when local mortician Bernie Tiede, aged 39, murders Marjorie Nugent, the 81-year-old millionaire heiress who he’s been companion to for over a decade. Linklater uses a documentary approach to “interview” the local townspeople about Bernie and Margie’s complicated relationship. What’s truly fascinating about these talking-head style interviews is that, while actors portray many of the townspeople, Linklater also includes interviews with some of the real residents of Carthage who knew Bernie and Margie.

The early afternoon screening incorporated introductory remarks from a representative of the JFK Archives at The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza. JFK: Breaking the News is a 2003 PBS documentary narrated by Jane Pauley about the struggle for news organizations in Dallas to relay accurate, timely information during the chaos and immediate aftermath of John F. Kennedy’s 1963 assassination.

Saturday night featured a double bill of movies chronicling the talents and determination of the depression-era debate team at Wiley College, an HBCU located in Marshall, Texas. Denzel Washington directed and stars in 2007’s The Great Debaters, wherein he portrays Melvin B. Tolson, the debate coach whose students defeated, in 1935, Harvard University’s elite debate team.

At least, that’s the movie’s version of events. In reality, the Wiley team, under Tolson’s guidance, defeated the then-reigning national debate champions at the University of Southern California. Harvard must have seemed a sexier opponent to either screenwriter Robert Eisele, Denzel Washington, or some nameless studio executive. While The Great Debaters is boilerplate biopic fare, the story it explores – like the documentary that played after it at ICFTX, 2008’s The Real Great Debaters – is an important part of Black (and American) history. Black Americans at the time couldn’t legally sit at lunch counters that served white people, but this group of young men and women achieved the highest honor in their chosen field despite living in a society that hated them.

One of the most sobering sequences in The Great Debaters comes when the team gets lost in the Texas country backroads and happen upon a lynching in progress. It would be less distressing if this disgusting practice of racial hatred had vanished from human activity. However, we have evidence of such an event happening as recently as the year 2022. We’ve progressed a great deal when it comes to racial equality, but we still have so, so much farther to go.

**********

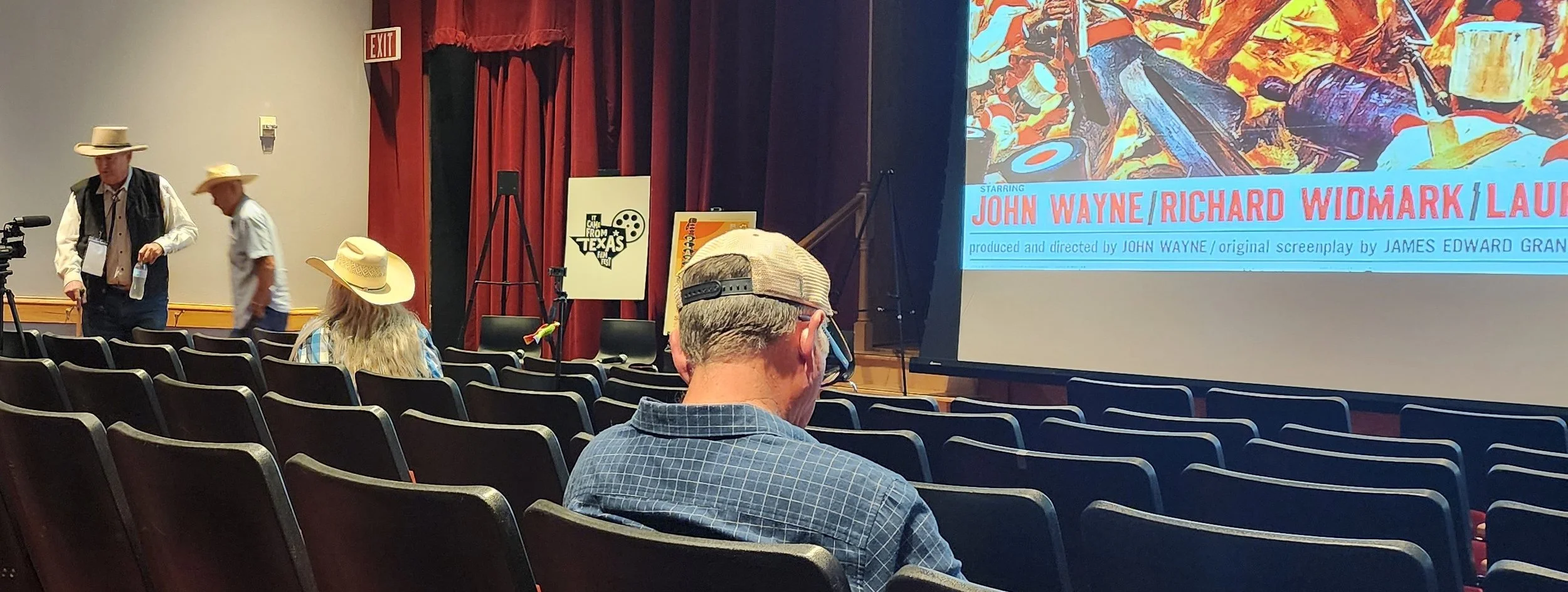

Sunday at ICFTX 2025 was Alamo day. Perhaps the most famous event in all of Texas history is depicted in the gargantuan, 202-minute 1960 Hollywood epic The Alamo, directed by John Wayne, with an unwelcome assist from Wayne’s mentor, John Ford. (Apparently, Ford showed up uninvited to the set and attempted to throw his weight around. Wayne sent him off to shoot unneeded second unit footage, and Ford’s contribution to the finished film was essentially nonexistent.)

Yep, this must be the place for The Alamo screening. (photo by the author)

In the wake of last year’s ICFTX, I raved about the George Stevens classic epic Giant. That film was a revelation to me in the way that a major Hollywood film of the 1950s tackled issues like racial discrimination. The Alamo, by comparison, seems creaky and regressive, but not without its subversive pleasures.

For one thing, the sexual chemistry between Richard Widmark’s Jim Bowie and Wayne’s Davy Crockett – especially after Crockett has sent his Mexican love interest, Flaca, away from the old Spanish mission before the fighting begins – is palpable. I found myself needing to double check to make sure Gore Vidal had nothing to do with the screenplay.

You can see English actor Lawrence Harvey, as Col. William B. Travis, trying as hard as he can to contort his mouth into shapes that will make an American accent come out. You can also see him failing miserably at the task. Sixties teen sensation Frankie Avalon flops around like a fish out of his teen-idol waters as Smitty, the youngest of the Alamo defenders.

The Alamo’s countercultural delights opened up further to me when I started looking at the central characters, who the movie insists are its heroes, as the villains. As I covered in my preview of ICFTX 2025, President James K. Polk essentially provoked a war with Mexico in order to take what is now Texas by force.

Say what you will about General Santa Anna – the dictatorial President of Mexico has been labeled an “uncrowned monarch” since his intermittent two-decade rule – but he only wanted back what the US government and military stole from him and his people.

Watching The Alamo as if Bowie and Crockett are the aggressors makes much more sense when Santa Anna’s forces TWICE try to resolve the standoff between the newly minted Texans and the Mexican army without bloodshed. The movie heralds these men’s eagerness for that bloodshed in defense of their honor like it’s a virtue.

Things become clearer still when you consider that one of the main issues of contention – which is only hinted at within the film – was that Mexico had recently outlawed slavery in their country. The Mexicans tried to work out a compromise, wherein the American nationals who had flooded into Texas after Polk’s provocation would be welcome to stay, but only if they swore off of slavery. That was a bridge too far for the white frontiersmen who would rather enslave other human beings than do a hard day’s work for their bread.

The pre-screening remarks for The Alamo during ICFTX were a frustrating litany of excuses for US military aggression in Texas and old-white-people shit about race. I’ll refrain from naming those speaking, but I heard the responsibility-deflecting old saw about how the majority of white people were too poor to afford enslaved people, as if that excuses, well, much of anything. Please tell me more about how the American Civil War was about heritage and not hate.

We were also told that John Wayne couldn’t have been prejudiced against Latinos, because, well, gosh, he was married to three Hispanic women during his life. (I’m also confident that some of Wayne’s best friends were Black.) I personally despise John Wayne because he eagerly participated in the Hollywood Blacklist of the McCarthy era. Wayne ruined several people’s livelihoods because they didn’t agree with his reactionary politics.

He was also an unofficial mascot for the odious idea of personal responsibility and rugged individualism that just so happened to gain momentum in the wake of the 1954 US Supreme Court decision that affirmed Black people were entitled to the equal distribution of public resources.

The 1969 farce Viva Max!, about a daffy Mexican General’s zany plan to recapture the Alamo (to impress his girlfriend) over a century after the famous battle was fought, closed out the fest. The fact that Peter Ustinov and John Astin both star as Mexicans in the film is slightly unsavory, but it’s hard to get too mad at a movie as silly and poorly made as Viva Max! is. Directed by Jerry Paris – who’s biggest contribution to film history is helming two Police Academy sequels –the movie pours on the wackiness, to fleeting comedic effect.

It Came from Texas 2025 will close out my film festival coverage for the year. As summer turns to fall, I and my fellow Texans impatiently wait for the temperatures to drop from sweltering to merely uncomfortably warm. Awards season is close. Along with it comes the crush of trying to see as much as possible before year-end voting is due.

As always, thanks for reading.

Movies are neat.