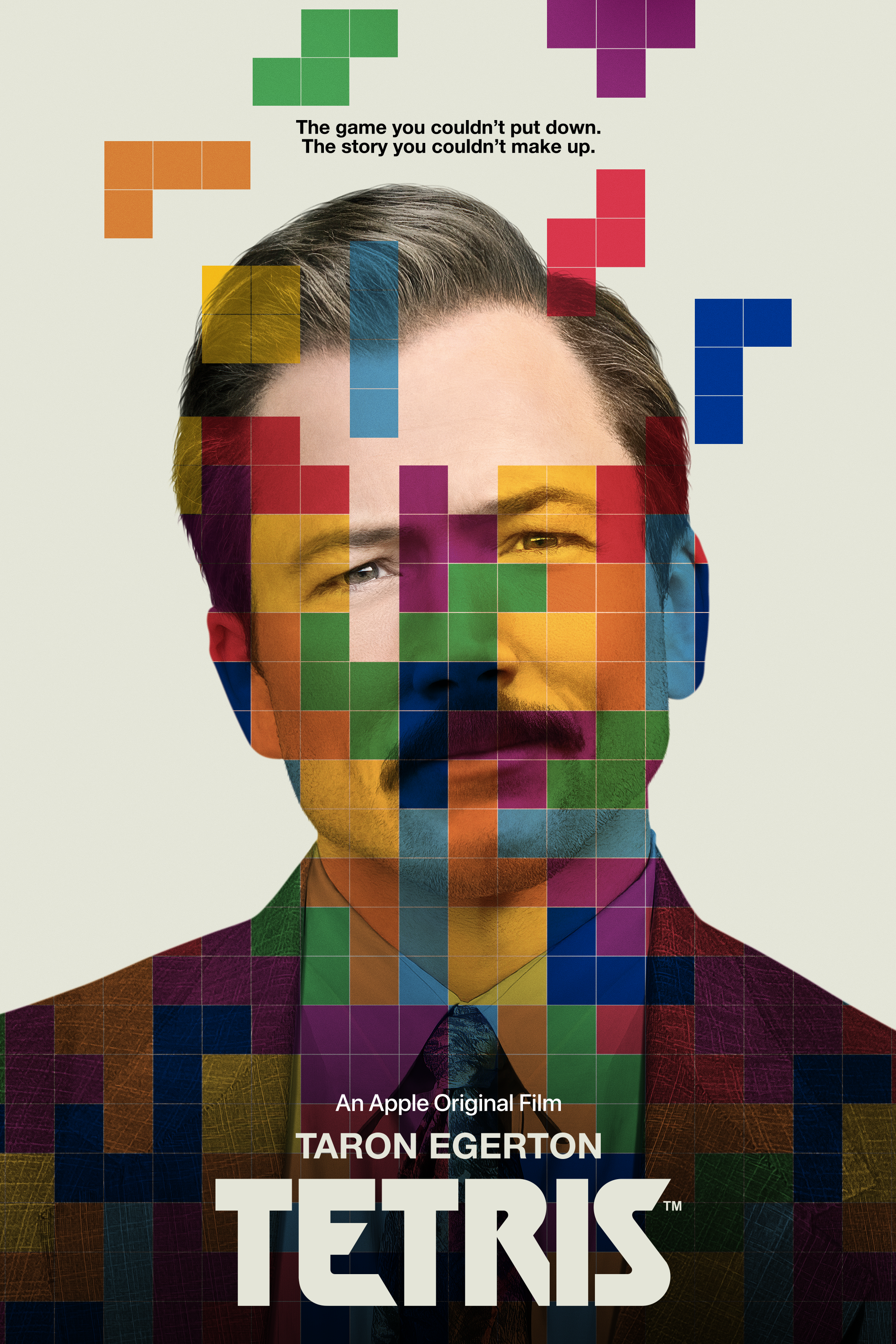

Tetris (2023)

dir. Jon S. Baird

Rated: R

image: ©2023 Apple TV+

You might be forgiven, especially considering Hollywood’s reputation, for expecting a movie titled Tetris to behave more like the 2012 screen adaptation of the popular board game Battleship and less like an intricately plotted spy picture, an 8-bit Bond. Thanks to Noah Pink’s tightly paced screenplay, Jon S. Baird’s crowd-pleasing direction, and a true story that the pair embellished in order to make it sing on the big screen, 8-bit Bond is what we get. Tetris is a raucous good time. It also has more on its mind than how seven geometric game pieces might fit together.

Tetris is yet more confirmation that my generation’s nostalgia is a hot commodity in entertainment right now. (I’m sure our collective disposable income and buying power has nothing to do with it.) In the past few years, I’ve watched a Netflix docuseries about the birth and popularity of home video game consoles in the 1980s and ‘90s called High Score, a docuseries dedicated to popular movies of the ‘80s and ‘90s called The Movies that Made Us – which is itself a spinoff of a series called The Toys that Made Us, about popular toy lines of the ‘80s – and now Tetris. I was eight years old during the events detailed in the movie. I played the game for hours on end once our house got an NES. (One of the best Christmas presents my brother and I ever received from our parents. Or maybe that one was from Santa, I can’t remember.)

Eight-year-old Josh had no idea of the elaborate and dangerous machinations involved in getting the little plastic game cartridge into our rural East Texas home. All I knew of the game’s provenance was the Russian-style onion domes featured in its artwork and, of course, the 8-bit versions of Russian folk songs featured on its soundtrack, (You’re already humming the main theme, aren’t you?)

In Pink and Baird’s telling, getting that game into hot little hands like mine (and millions of other kids and adults alike) took nothing less than a showdown between the two biggest economic and societal regimes of the period: Western-style capitalism and Soviet-style communism.

Invented in his spare time by Russian computer engineer and programmer Alexey Pajitnov, the Tetris computer game proved wildly popular in Pajitnov’s home country. It made such a splash that Robert Stein, of Andromeda Software, licensed the rights to the game, who then sold those rights to a British media mogul named Robert Maxwell and his conglomerate Mirrorsoft, in exchange for royalties on each unit sold.

When our hero, Henk Rogers, plays a demo of the game at a Las Vegas consumer electronics trade show, he falls instantly under Tetris’s spell. His own game, GO – a version of an ancient Chinese strategy game more complex than chess – is a dud, and Henk is convinced that Tetris will be a guaranteed phenomenon.

Do you remember when Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace was released and one of the main criticisms was that a tentpole sci-fi action blockbuster was ostensibly structured around a galactic trade dispute? A movie about a trade dispute (minus the galactic scale) is precisely what Tetris delivers. I’m reluctant to give a point-by-point breakdown of the conflict, because it has a lot to do with efforts to secure rights not simply to the game Tetris, but rights to the arcade, home computer, and game console versions of the IP. I’m confident that if I get too granular about the plot, I’ll bore you to tears, which is the exact opposite effect the actual movie had on me.

When Henk is double crossed by Mirrorsoft – specifically, Robert Maxwell’s son, Kevin, the new CEO of Mirrorsoft who is desperate to prove to his father that he has the killer instincts of his old man – over the rights he thought he obtained for Tetris at the trade show, Henk travels to the Soviet Union to strike a new deal. Having already built inroads with the head of Nintendo over his tenuous rights to release Tetris in Japan, Henk is granted access to Nintendo’s inner sanctum, where he sees their latest invention, the Game Boy. This groundbreaking development introduces a new set of rights for Henk to secure: handheld.

In director Baird’s hands, the contract negotiations for these various rights are fodder for high intrigue. The players are Henk’s scrappy firm, Bulletproof Software, the Maxwells’ powerful Mirrorsoft – the elder Maxwell counts Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev as a personal friend – and the Soviet software “company” ELORG, which holds the licensing rights to Alexey’s game.

(As my scare quotes indicate, ELORG, Alexey’s employer, isn’t really a private company, since private enterprise was antithetical to the Soviet ethos, but is actually a government entity. Under the Soviet communist system, Alexey isn’t allowed to profit personally from his creation. Instead, the money made from licensing Tetris to these Western companies will be used to further the glory of the Soviet people and empire.)

Tetris deftly uses the brawl for licensing rights to a video game as a way to critique the corruption inherent in both unadulterated capitalism and Soviet-style communism. Alexey being reduced to an onlooker over the fate of something he created is a sick joke. We see the security state of Soviet Russia exemplified through its opaque bureaucracy. One of the bureaucrats, Nikolai Belikov, has dedicated his life to the ideal of Soviet communism. He delights in the petty power play of pretending not to speak English upon his first meeting with Henk. Belikov quickly learns how much his devotion to Russian glory is worth when a bribe from Western interests dictates the orders coming from his superiors.

That bribe – you can probably guess which of the players I’ve described issues it – is a damning indictment against the capitalist system that rewards using private riches in order to game the system in one’s favor. When Kevin, who is an easy villain to hate (he insists on being called “Mr. Maxwell” whenever someone refers to him simply as “Kevin”), tries to use his father’s billion-dollar fortune as a signifier of virtue, he is reminded that nobody accumulates that much wealth without using unsavory tactics to get it.

There is also a (not-so-subtle) critique running throughout Tetris of the incompetence that the privilege and wealth of corrupt capitalism breeds. Kevin is soft. He didn’t have to work for what he has been handed, which is evidenced by his go-to retort whenever someone accuses him of not being familiar with the day-to-day operations of his father’s empire. Kevin runs a multinational corporation, he’s quick to point out, so he doesn’t have time to know the fine details of every operation. What that really means is that the little twirp doesn’t know the fine details of any of the company’s operations.

Baird works overtime to make Tetris sing in ways that the contract dispute plot might not suggest. His visual effects team incorporates charming 8-bit graphics transitions throughout the movie to give it personality. The height of these effects comes during the climactic car chase sequence, when Henk and his entourage must get to the airport before the KGB can stop them from leaving the country. As the cars race thorough the Moscow streets, they turn into 8-bit versions of themselves, pixelating each time they crash into another object.

This race-to-the-airport sequence is evocative of the similar climax in Oscar Best Picture winner Argo, only in Tetris there is no need to worry about the low-key Islamophobia present in Ben Affleck’s 2012 crowd-pleaser. Instead, Tetris goes after institutional power, and, considering how madman Vladimir Putin is doing everything in his power to turn Russia into a police state that Stalin would have envied, it’s clear that this story, set three+ decades ago, is sadly still relevant today.

(You will have cause for concern if you’re worried about verisimilitude. Both Henk Rogers and Alexey Pajitnov have confirmed in interviews that while they were consulted on some aspects of the screenplay for accuracy, there are plenty of elements – including the car chase – that were zhuzhed up using old-fashioned Hollywood showmanship.)

Welsh actor Taron Egerton goes for broke with his portrayal of the indefatigable Henk Rogers. If there are a few fleeting moments when the energy of Tetris begins to flag, Egerton never fails to pick up the pace with his wily, wide-eyed Henk. This is my first encounter with Egerton’s work, who gained a lot of attention (plus a Golden Globe nomination and a BAFTA win) for his portrayal of Elton John in Rocketman, the 2019 biopic of the singer. It should be noted – and the movie itself does note – that the real Henk Rogers has Indonesian heritage. Egerton is somewhere between mayonnaise and Wonder Bread on the whiteness scale, but it seems that Rogers is happy with the casting, so I’ll leave the whitewashing issue there.

Russian actor Nikita Efremov brings pathos to the film as Tetris inventor Alexey Pajitnov. Alexey faces down the demons of what happened to his own father under Soviet oppression when his actions threaten the lives of his children. Without spoiling too much, actress Sofia Lebedeva pulls off a tricky acting-within-the-acting feat as Sasha, a translator who helps Henk with his negotiations at ELORG.

Irish actor Anthony Boyle got the memo letting him know that his character, the snotty Kevin – excuse me, Mr. Maxwell – should be as insufferable as possible. Inexplicably, the production team for Tetris felt the need to stick actor Roger Allam in a fat suit to portray Kevin’s father, media mogul Robert Maxwell. Allam has been nominated six times (with three wins) for the Laurence Olivier Award, but was there nary a single fat actor who could have tackled the role? At the very least, the character’s size isn’t a factor in the actual story.

In the denouement of Tetris, it’s implied that good, old-fashioned consumerism is what caused the Iron Curtain to finally fall. Who knew that buying a video game could end authoritarian oppression? While that Hollywood ending was a bit too facile for my taste, Tetris is a hell of a good time. It offers a critique of both capitalism and communism, how prone both systems are to corruption and greed, while it simultaneously entertains with a level of suspense and intrigue usually reserved for a character like 007.

Why it got 3.5 stars:

While I have a few minor quibbles with Tetris, it’s undeniably an infectious, crowd-pleaser of a movie. Consider me a certified Taron Egerton fan.

Things I forgot to mention in my review, because, well, I'm the Forgetful Film Critic:

- There are several moments in the movie that are pure magic. One is Henk’s initial encounter with the game. The next is when Henk points out to his wife that their home is library-quiet because the kids are so enchanted by Tetris. The third is Nintendo’s unveiling to Henk of the Game Boy. As a former Game Boy owner, the filmmakers capture the excitement and wonder of seeing this video game marvel for the first time.

Close encounters with people in movie theaters:

- I saw this at SXSW 2023, and there was a buzz in the air at the packed screening I attended. The energy in the room as the film played was palpable. If you read my SXSW coverage, you’ll already know that the real Alexey Pajitnov was in attendance. So was the real Henk Rogers. They spoke briefly after the screening. I had to hustle out of the theater in order to make my next screening, so I’ll forever regret not expressing to Alexey how much his game enriched my life as a child. I watched it again (in preparation for this review) at home with Rae. It was as enjoyable on the couch as it was with an amped up crowd. Tetris is now currently available exclusively with an Apple TV+ subscription. I’m assuming it will eventually be available for rent or purchase on most digital streaming platforms.

The real Henk (left) and the real Alexey (right) participate in a Q&A after the Tetris world premiere at SXSW. (photo by the author)