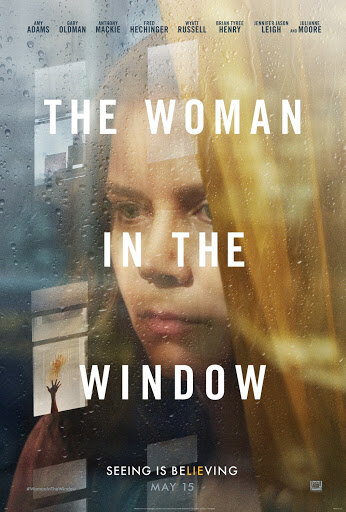

The Woman in the Window (2021)

dir. Joe Wright

Rated: R

image: ©2021 Netflix

The Woman in the Window is so indebted to the work of director Alfred Hitchcock that a scene from one of the Master of Suspense’s movies is incorporated into the film itself. It’s the most avant-garde sequence Hitchcock ever directed, the dream sequence from Spellbound in which he collaborated with surrealist artist Salvador Dalí. The other two central touchstones in Joe Wright’s adaptation of the bestselling novel by pseudonymous author A. J. Finn are Rear Window and Psycho. Those movies never make an appearance in Woman in the Window, but you can feel their presence hanging very heavy over every element of the new thriller.

As talented a director as Joe Wright is – I remember quite liking his adaptation of the novel Atonement and his thriller Hanna, less so his Oscar bait-y Darkest Hour – he’s no Alfred Hitchcock. Woman in the Window is cheap Hitchcock pastiche. By the gory final reel, it becomes rather distasteful Hitchcock pastiche. Its twisty nature is derivative and it presents a troubling, retrograde vision of mental illness.

Anna Fox is trapped in her Manhattan brownstone apartment. Instead of a broken leg keeping her confined, it’s her fragile mental state. Anna suffers from agoraphobia, a crippling anxiety disorder which causes Anna to have panic attacks any time she leaves the perceived safety of her home for even a few minutes. Her therapist is worried about how she is responding to her new meds, and Anna liberally mixes the prescription drugs with alcohol, despite the warnings on the labels advising against it.

She is estranged from her husband, Edward, who has custody of their daughter, but the two speak on the phone at least once a day. We get the vague sense that Anna has suffered some deep trauma, but in order to save one of the biggest twists of the movie, I’ll stop there.

Anna’s precarious situation falls apart completely when she witnesses (through the telephoto lens of her camera, no less) a violent crime in the apartment of her new neighbors across the street, the Russell family. Before the deadly event that serves as the crux of the movie’s plot, Anna meets each member of the family: shy and sensitive teenager Ethan, domineering and abusive father Alistair, and mother Jane. Or is the woman who Anna spends an evening with in her apartment actually Jane Russell, or an imposter?

The fact that the character shares her name with the Hollywood Golden Age actress leads to one of the most laughable plot points of the movie. In an attempt to put the pieces together when she learns a completely different woman is actually Jane, Anna attempts to Google her new neighbor. The only search results she can initially get is information about the star of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. We’ve all had the experience of a tough Google search; that doesn’t mean you should work it into your murder mystery.

The filmmaking from Wright and his collaborators is solid, if slightly heavy-handed (the Hitchcock stuff becomes unbearable pretty early on). Amy Adams, as Anna, does her best to elevate the schlocky material with her formidable talent. Anna is a fractured and tortured person, and Adams conveys that with an off-kilter, wild-eyed performance. Gary Oldman is darkly sinister (with a shock of white hair, no less) in his few scenes as Alistair, a surprising role for him to take on, considering the actor has faced accusations of brutal domestic violence himself. Anthony Mackie, Wyatt Russell, Brian Tyree Henry, and Julianne Moore all turn in strong supporting performances. Jennifer Jason Leigh is wasted in a few scenes as the “real” Mrs. Russell.

I suspect the real problem with The Woman in the Window is the source material. The novel by Daniel Mallory, who published it under the nom de plume A. J. Finn, for reasons which will become apparent soon, was an instant hit. It debuted at number one on the New York Times Best Seller List, a rare feat for a first novel. Then Ian Parker published an engrossing but hardly flattering profile of Mallory in The New Yorker, which basically suggested that Mallory is a Tom Ripley-esque conman. The least of Mallory’s alleged transgressions is that he borrowed heavily from the 1995 psychological thriller movie Copycat for the plot of The Woman in the Window. Parker surmises that Mallory had to go the secret-author route when shopping his novel to publishers because, since his name was so poisoned within the publishing world, no one would want to buy the rights once they found out he was the real author.

In the New Yorker piece – which I highly recommend taking the time to read – Parker busts Mallory for, among other things, lying to coworkers about having a terminal brain tumor, lying about his mother dying from cancer, and lying about his brother taking his own life. He has claimed to have two doctorates – Parker confirmed with Mallory’s alma mater that he never completed any doctorate program – one of which focused on author Patricia Highsmith’s Tom Ripley series of novels in which a master manipulator and liar insinuates himself into high society through deception. Seriously, Mallory seems like a very sketchy dude.

I haven’t read The Woman in the Window, but from the research I’ve done, in addition to its blatant larceny of elements of Copycat, it wears it’s Hitchcock influences a little too loudly and proudly. Chicago-based playwright, screenwriter, and actor Tracy Letts – who also turns in a supporting performance as Anna’s therapist in the movie – adapted the novel for the screen, and both he and Joe Wright play into the Hitchcock pastiche elements of the story, to the movie’s detriment. I don’t want to spoil the (15th or so) twist we get by the end of this thing, but the Psycho connection turns rather ugly and off-putting; I was sufficiently sickened by the picture’s climax. The film limply ends with the lazy our-protagonist-comes-out-the-other-side-stronger trope. The final shot of Anna smiling bravely on moving day, as she leaves her personal prison for the last time, is a step away from all-problems-are-solved-in-30-minutes-or-less sitcom territory.

The unreliable narrator device has a rich history in storytelling. The narrators in Fight Club and Rebecca, and Amy Dunne in Gone Girl are only a few examples. There’s also Rachel Watson in The Girl on the Train, another recent and popular thriller novel (which was also turned into a lackluster movie) that Woman in the Window rips off. Anna Fox is certainly an unreliable narrator, but Joe Wright’s film is a poor, distasteful entry into the genre.

Why it got 2 stars:

Kyle Turner at GQ has made the argument that, contrary to overwhelming critical opinion, The Woman in the Window is actually a camp masterpiece. I don’t agree. I think it’s an artistic misfire, but I will admit, reading his piece made me want to watch the movie again through that lens.

Things I forgot to mention in my review, because, well, I'm the Forgetful Film Critic:

- I find it interesting that Woman in the Window can so easily be read as a commentary on our past year of pandemic living. Anna is a shut-in, reflecting how many of us have felt since COVID took over our world. This can’t be the case, though, because the movie was shot in 2018, but it always amazes me how much a viewer’s current state can affect what the viewer gets out of the movie-watching experience.

- One thing I’m sure was intentional is the commentary on how we all look at the world through social media, particularly via screens. The movie teases that connection, but it never really explores it in a satisfying way.

- One moment that did work for me was the staging surrounding the final reveal about Anna’s past. The set design and special effects in that moment are both very effective.

Close encounters with people in movie theaters:

- The Woman in the Window is available exclusively on Netflix.