The contemplative, roving camera of Terrence Malick has been loosed upon the breathtaking beauty of Europe. But the grandeur of the sweeping vistas, open fields, and European architecture comes at a price. Malick’s film A Hidden Life begins in 1939 at the outbreak of World War II and ends in 1943, well before the horrors of that conflict ended. We see little of the war’s devastation, though, because A Hidden Life focuses on historical figure Franz Jägerstätter, an Austrian man who refused to fight in Hitler’s army. The picture is a meditation on the price of resistance, for both Franz and those closest to him. It also wrestles with religion and draws parallels between the fervor of the German and Austrian people for Hitler’s cause and America’s current political climate. A Hidden Life does all this in Malick’s inimitable, transcendent elliptical style.

Viewing entries tagged

Terrence Malick

The phrase “found it in the editing” describes a perilous method of filmmaking. Basically, it’s what happens when a movie has been shot with no clear vision – or there is a voluminous, unwieldy amount of footage – but during the editing process, the filmmakers are able to shape a story that is much better than the raw materials would suggest. A famous example of this is Woody Allen’s Annie Hall. That movie initially had very little to do with the relationship between the two leads, but during cutting, Allen and his editor created one of the best romantic comedies of all time. More often than not, though, this approach leads to a muddled mess.

Terrence Malick’s creative process lends itself to this kind of metamorphosis in the editing room. The notoriously private director shoots and shoots, sometimes for years, and hones his narratives in the cutting room, also sometimes for years. Song to Song clearly follows this pattern. In a rare interview to promote the picture, Malick said the original cut of the film was eight hours long. That’s a far cry from the 129-minute final version. Song to Song is also a far cry from the beautiful transcendence of his best films, like Days of Heaven or The Tree of Life. It’s not a complete mess, but it’s a disappointment to be sure.

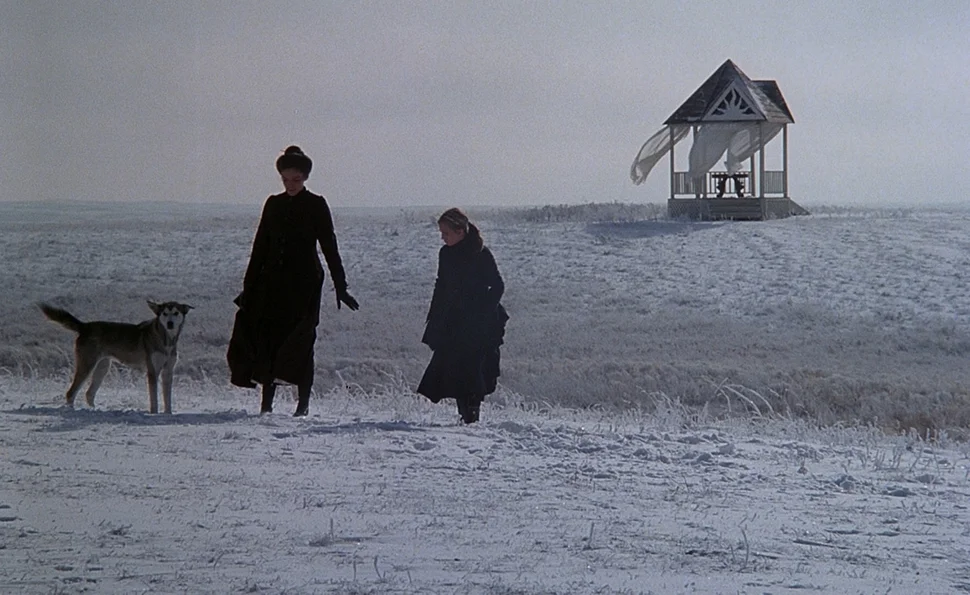

The story is simple, if unconventional. It’s the early 1900s. Two down-on-their-luck lovers, Bill and Abby, and Bill’s kid sister, Linda, leave the industrial nightmare of Chicago and find work on a farm in the Texas panhandle. The rich, ailing farm owner falls for Abby, and wants to marry her. Bill and Abby decide to cash in, since the farmer probably won’t live much longer. It’s not like the two lovers will need to stop seeing each other, since they hide their relationship from everyone they meet by telling people they are brother and sister.

From that synopsis you might assume Days of Heaven is a standard tale of love, deception, and betrayal. With director Terrence Malick at the helm (who made the even more experimental The Tree of Life), standard never enters the equation. From that basic plot, Malick assembles a quiet meditation on the infinite beauty of the nature that surrounds humanity, and our determination to ignore it in pursuit of material gain. The virtuoso photography of cinematographers Nestor Almendros and Haskell Wexler, and Malick’s lyrical structure combine to make Days of Heaven a superlative example of the 1970s New Hollywood movement.

It’s hard to overstate just how stunning the cinematography for Days of Heaven is. The film won that award at the 1979 Oscars, and because Almendros was listed as principle photographer – Wexler came on when Almendros had to leave to shoot another film – he was the only one to receive the award. Because of the slight, Wexler famously wrote a letter to Roger Ebert in which he described sitting in a theater timing all his footage with a stop watch, proving he was responsible for more than half the picture. It’s easy to see why Wexler was so passionate about it. Practically any frame in the movie could be transferred to a canvas and hung in a gallery, but one shot is particularly breathtaking. It only lasts about ten seconds, but the image of an impossibly huge thunderstorm sweeping across the landscape will give you pause. On the left of the frame is a relatively tranquil, blue sky while the right side of the composition is dominated by the angry tempest invading like a marauding army. Much of the film was photographed at “magic hour,” those fleeting moments at dawn and dusk when the sun paints the sky with beautiful pink and purple hues. The skill of both men to catch those gorgeous colors on film with just the right stock and filters is awe-inspiring.